Business English, Professional English, Legal English, Medical English,

Academic English etc.

Online Journal for Teachers

ESP World

ISSN 1682-3257

http://esp-world.info

English for Specific Purposes

|

Travel

and Tourism Students’ Needs in Valencia

(Spain):

Meeting

their Professional Requirements in the ESP Classroom

Jesús García Laborda,[1]

Universidad Politécnica de Valencia

For many years Tourism companies and universities have ignored each other in the Valencian area. Valencia is one of the most important tourism areas in Europe. It is easy to understand the need to build bridges between companies and students’ university requirements if universities really want to get funding for their research and if students are to be hired in the future (Minnis, 1997). The modern university requires these funds not only to survive but also to increase its research activity and potential. The Universidad Politécnica de Valencia (UPV) at Gandía has always shown great interest both in its alumni careers and research development. Only last year the Faculty of Tourism became a research centre of the World Tourism Organization. At the moment, it has over 300 students and several ongoing research projects. Thus, some members of the teaching staff have started seeking ways to improve the learning environment. They try address the students’ needs to fit in the real business world through computers (Searle, 1999) and professional skills (Giffard, Guegnard, and Strietska-Ilina, 2001) in the language classroom (Watts, 1994). ESP World Journal has earlier presented the first of a number of articles that were published last year describing the results of some of these educational efforts (García Laborda, 2002a).

The UPV at Gandía is currently operating two experimental educational programs of new technologies applied in teaching students of tourism. Basic Computer Introduction in Tourism is intended for students in the first year, and Linguistic and computer implementation in FL learning[2] (Adecuación lingüística y en nuevas tecnologías del aprendizaje de inglés para la diplomatura de Turismo) is a 2-year program.

The main purpose of this paper is to describe the basic findings obtained as a result of the implementation of both projects. As the reader will understand, the results offered in this paper are tentative and will need further study. In short, the findings in this paper revealed their correlation with some of the issues brought up in García Laborda (2002a).

The pilot study

In the 2001-2002 academic year two professors ran the Basic Computer Introduction in Tourism pilot study with the students described in this paper. At that time work with new technologies was explicitly instructed by one of them. It presented a very basic approach to the use of Word and Power Point programmes through such activities as individual presentations and group work. The results showed greater motivation and just about the same level of language use (according to the European Foreign Language Portfolio).

Linguistic and computer implementation in FL learning

The official beginning of the project was in November 2002. Thus, the following description summarizes the findings and results of the first year of its instruction.

Objectives

The main objectives of this study were to observe:

(1) whether EFL Turismo students use adequate language and professional learning strategies[3] as required in their field of expertise;

(2) the types of L2, L3 and professional learning strategies being acquired; and

(3) whether teaching strategies explicitly facilitated their L2, L3 and professional skills learning.

Sample population

The pilot study was implemented as a part of the Europa Project (teaching improvement project run at U. Politécnica de Valencia). The total number of students involved was 92 (out of 106). Most of the other students registered in the class dropped out or withdrew in the first two months. Overall, the actual dropout rate during the experiment rounds up to 15%. These learners were integrated in 3 second year classes of English for Tourism.

Initial data on use of strategies

The current study was carried out with about 80 second year students of English at the College of Travel during the academic year 2001-2002. The data hereby collected was obtained in two meetings during regular class hours. The results can be summarized in the following list:

Teaching orientation: Teacher – group dialogue

-

Most students feared foreign languages due to negative past experiences.

-

Many had done little or no group work in their previous English classes.

-

Despite what most professors expect in college, many of these students had had little contact with new technologies (both as creators or users).

-

They thought they might need some professional skills preparation before their period of study – work in the second year of college, but they had received none up to that moment.

-

During their previous schooling they had done few presentations & little pairwork, and consequently, they showed limited speaking abilities.

Experiential strategy development

The sequence described in this paper states the following process:

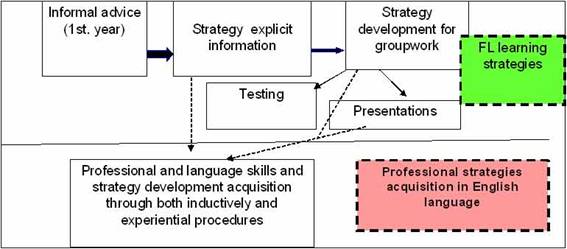

Figure 1. Strategy development in a two-year plan

It is understood that any plan for strategy implementation should be preceded by some type of informal advice stating some of the most relevant strategies to be developed. However, during the second year students have to be told explicitly of the need, potential and variety of learning and working strategies available and also desirable for their prospective careers. Thus, they need to obtain information on what and how to use these developmental strategies. To address this need, the English professors of Tourism at the UPV wrote a full book (García Laborda, 2002b) devoted to group work, learning strategies, use of learning tools and propositions for further research. The English II professors also gave assignments to reinforce the acquisition of both professional and academic strategies. As it can be seen in figure 1 , testing is a part of the process as the researchers who prepared the program believe that just like language is acquired consciously and subconsciously, so are strategies.

Professional cooperation through progressive cooperative learning

One of the most significant and attractive goals for the implementation of the final program has been the emphasis on the incorporation of key elements of cooperative learning as stated above in 4 phases (2 to 3 years):

A.è presentations & simple projects

B.è electronic brochures, videos & web pages

C. Outcome Assessment:research-based evaluation

The implementation process has a double implementation level. As the assignments are given, the four phases will be included as appropriate, stating very clearly how and in what way the cooperative work is assessed and evaluated. Observe the evolution diagram for an assignment to produce a video as an example.

| Creating a video advertising Gandía Beach |

Pre-collaborative: small task assignment – video recording, data gathering, script preparation |

| Collaboration: final script, rehearsal, recording |

|

| Post-collaborative activities: self-evaluation, personal outcomes and learning |

|

| Outcome Assessment: changes; process and product analysis, evolution; and research |

Figure 2. Cooperation phases for the creation of a promotional video

Results

Naturally, the researcher strongly believes that the experiment so far has produced significant results that can be analysed from three perspectives: first, change in working and learning conditions, second, qualitative changes in project production, and third, improvement in curricular results.

| Inicial Conditions |

Evolution Conditions |

Final state |

|

| English |

Lack of professional & language learning Strategies Teacher directed strategy acquisition |

Group work strategy acquisition Basic professional strategies Individuals strategy acquisition |

To be seen upon the final implementation of the program in the 2003-4 school year |

| French |

Lack of professional & language learning strategies Contextual (subconscious) strategy acquisition |

Individuals strategy acquisition Contextual (subconscious) strategy acquisition |

Individual Language Learning Individual language testing Contextual (subconscious) strategy acquisition |

Figure 3. Evolution of learning conditions as compared to those showed by the 3rd year French students in the academic year 2001-2002.

To obtain a clearer picture of the progress, the researchers compared the students’ evolution on the various phases of the pilot study with the data gathered from the French III students (figure 3)[i]. The first clear distinction is that while French III students could develop strategies individually and through contextual acquisition (subconsciously), English II students acquired them both consciously and subconsciously and both individually and through cooperative tasks. It also became evident that while in the past the acquisition would be in language learning, students now also acquire professional habits and skills through the program [4]. This can be better seen in the following diagram showing the students’ achievements during the same period of time

| Inicial Conditions |

Evolution Conditions |

Final state |

|

| English |

Professional presentations 1st. Certificate grammar Intermediate level reading skills |

Electronic brochure Basic professional marketing videos Web pages CAE grammar Non simplified readings |

To be seen upon the final implementation of the program in the 2003-4 school year |

| French |

1st. Certificate grammar Rehearsed Monologues Use of Intermediate level simplified readings |

Individual speech (student teacher) Rehearsed presentations Use of Intermediate level simplified readings |

Individual speech Rehearsed presentations 1st. Certificate grammar |

Figure 4. Evolution of group and individual achievements as compared to those showed by the 3rd year French students in the academic year 2001-2002.

Academic achievements

As stated in the second section of this paper, one of the major concerns of implementing the program was coping with deficiencies observed up to now in the curricular program. Of these, dropout and exam failure were the most important. Indeed, it is understood that this project should aim to attain the general improvement in the core subject (English II). The following two diagrams represent the results obtained in the pilot study. The first (figure 4) shows the final grades obtained by the participating students. Final results evidence an overall improvement compared to previous years.

However important these results may be, there were some other concerns involved in the program implementation such as the dropout rate, professional integration of school projects, or the student’s professional profile creation.

| Inicial Conditions |

Evolution Conditions |

Final state |

|

| English |

Language usedevelopment 20% Dropout 75% pass or better grades |

Professional skills development 20% Dropout or lower 80% pass or better grades |

To be seen upon the final implementation of the program in the 2003-4 school year |

| French |

Grammar centered study 35% Dropout 45% pass or better grades |

Grammar centered instruction does not seem to lead into learning 35-40% Dropout 40% Pass or better |

Urgent need of FL learning after graduation High dropout 80% Pass or better (in real percentage, about 35%) |

Figure 5: Other curricular results by the June exams of previous years.

In relation to the curricular results, the researchers observed that most of these aspects were covered by the implementation of the program. Probably, the most important change is the dramatic decrease in actual dropout rate (that was observed after the first two months). In addition, the researchers handed a questionnaire to the students at the end of the semester, and most of the respondents were positive about their learning at this experimental stage.

Discussion and conclusions

Overall, researchers consider this pilot study to be very friutful. From the recorded observations and professional and academic results it can be concluded that the inclusion of professional and language learning strategies development in the academic process provides for both group and individual improvement.

From the class observations, tutorial conversations and questionnaire analysis it was perceived that the worst problem students came across was the extra load that a program of such nature requires. Students feel that the number of projects and exams exceeds the work load they would expect from the subject (English II). Therefore, projects will probably be grouped in the future assuming that the electronic brochure can be included in the web page. Obviously, the load will not diminish but the professors think that students’ feeling of extra work load may be reduced and, as a consequence, motivation would rise. In fact, motivation is one of the major assets of this scheme. Students who finished their assignments and passed their exam showed greater satisfaction in their performance than their counterparts from the year before. Additionally, they considered that the learning and professional strategies acquired through the course would be very valuable for their future careers. They also consider that both types of strategies can be combined and contextualized to their own benefit, and that they use some of these strategies more often than before the course.

In relation to the language, the results evidenced a slight improvement compared to the traditional class. For the upcoming program implementation, some of the language related elements, such as the reading book, will definitely change becoming more adapted to their reality. Actually, a new book of readings is presently being prepared and will hopefully be published by November 2003.

To conclude, the study has proved to be very valuable, and worthwhile despite the extra effort it required. In relation to the program implementation, the solutions and proposals discussed in this paper are under consideration. Hopefully, the changes we are going to introduce will facilitate learning and make it a more effective and enjoyable experience. Only time and experimentation will provide answers to the questions that inevitably arise with innovation. In this sense, this paper is only a first approach to be continued by further study and work in a near future.

References

Crockett, L. L. (2002) Real-World Training To Meet a Growing Demand. Techniques: Connecting Education and Careers; v77.4: 18-22.

García Laborda, J. (2002a) Incidental Aspects in Teaching ESP for Turismo in Spain The Turismo Learner: Analysis and Research’ ESP World, v.3 retrived on October 11, 2003 at http://www.esp-world.info/Articles_3/ESP%20for%20Turismo%20in%20Spain.htm

García Laborda, J. (2002b) ‘Estrategias de Aprendizaje: Una herramienta básica para estudiar idiomas’ in Jesús García Laborda (Ed.). ¿Por dónde empiezo? Técnicas de aprendizaje de lenguas para estudiantes de Turismo. Valencia: Servicio de Publicaciones: UPV.

Giffard, A.; Guegnard, C. and Strietska-Ilina, O. (2001) ‘Forecasting Training Needs in the Hotel, Catering and Tourism Sector: A Comparative Analysis of Results from Regional Studies in Three European Countries’. Training & Employment; n42.

Minnis, J. R. (1997) Economic Diversification in Brunei: The Need for Closer Correspondence between Education and the Economy. Chinese University Education Journal; v25.2: 117-36.

Searle, J. (1999) Online Literacies at Work. Literacy & Numeracy Studies; v9.2: 1-18.

Watts, Noel (1994) The Use of Foreign Languages in Tourism: Research Needs. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics; v17.1: 73-84.

[1] I want to thank Antonio Forés López for his cooperation in the implementation of this project.

[2] The researcher understands learning as the process that serves to change the way of seeing, experiencing, and conceptualising new things in his daily life (for instance, group work, search engine use, what can help to run a travel agency or what to do if there is overbooking at a hotel) instead of certain amount of items that anyone has acquired (for example, when to use past perfect). In this article learning goes far beyond foreign language.

[3] Professional skills are not just those used in relation to foreign language learning. It refers to the student’s own practice and working needs as a Travel and Tourism professional.

[4] Please refer to footnote 3.

[i] From Garc?a Laborda (2002 b)

Home ESP Encyclopaedia Requirements for Papers Guidelines for Authors Editors History